Fish Iowa - Fish Species - Gizzard Shad

Characteristics

Gizzard Shad have the typical herring body shape with a deep, oblong body that is strongly compressed laterally. Color ranges from bright silvery-blue on the back, silvery sides and a dusky-white on the belly. A dark shoulder spot is common on younger fish, but may be absent from adults. The front of the head is rounded with a sub-terminal mouth. Teeth are absent. There are about 190 rakers on the lower limb of the first gill arch. The eyes have adipose eyelids with vertical slits. Body scales are cycloid with no lateral line present. The ventral scales are keeled. Dorsal fin rays number 10 to 12 with the last ray elongated into a thin whip-like filament. This fin is inserted slightly behind the pelvic fin. An auxiliary process is present at the base of the pelvic fin. The anal fin has 27 to 34 rays, and the caudal fin is deeply forked.

Foods

This species is an omnivorous filter feeder taking both phytoplankton and zooplankton, which are then ground in the gizzard-like section of the gut. Some bottom material is often ingested while feeding; hence, the name mud shad or mud feeder.

Expert Tip

Shad make great bait for catching Channel Catfish.

Details

Gizzard Shad are common in lakes, oxbows, impoundments, sloughs and large rivers with basic or low gradients, but reaches greatest abundance in waters where fertility and productivity are high. It avoids high gradient streams and rivers in the mountains and rivers without large, permanent pools, but can tolerate moderately turbid and occasionally even brackish or salt waters. The Gizzard Shad prefers living in open water, at or near the surface.

In Iowa, this species is synonymous with mud, preferring sluggish, soft-bottomed waters. It has benefited from the construction of upstream reservoirs in the larger rivers in its range.

Gizzard Shad spawn in shallow backwaters or near the shore. The fish are random, nocturnal group spawners with no care given to the young. Eggs are released near the surface of the water from late April or early May to early August at 50 to 70 degrees. The eggs are adhesive and sink. The females produce up to 400,000 eggs that are about .03 inch in diameter.

Shad are intermediate hosts for several species of the glochidiad stages of mussels and have economic importance in the protection of freshwater mussels with commercial value.

Shad commonly reach 4-inches long during the first year of life. The maximum size in Iowa is about 9- to 14-inches.

Gizzard Shad have little value as a food-fish and are seldom taken by hook-and-line. Its flesh, and particularly the gizzard-like stomach, are occasionally fermented to use as catfish bait. Dense shad populations provide great forage as young for other predatory fish, and their schooling behavior during the first year make them easy prey for larger fish. Some controversy surrounds this forage value, however, as shad quickly outgrow the vulnerable forage size and rapidly reach pest levels in some closed watersheds or when predator populations are insufficient to control their numbers. Evidence is strong that shad compete with young bluegill for food, and when populations reach very dense levels, bluegill survival is lowered. At that time, removing the while fish population and restocking game fish species, particularly in small lakes, is the only way to restore acceptable fishing. Massive die-offs of young and yearling shad are commonly reported after spring ice-out as a result of their susceptibility to fluctuating water temperatures.

Recent stream sampling information is available from Iowa DNR's biological monitoring and assessment program.

Sources:

Harlan, J.R., E.B. Speaker, and J. Mayhew. 1987. Iowa fish and fishing. Iowa Conservation Commission, Des Moines, Iowa. 323pp.

Loan-Wilsey, A. K., C. L. Pierce, K. L. Kane, P. D. Brown and R. L. McNeely. 2005. The Iowa Aquatic Gap Analysis Project Final Report. Iowa Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, Iowa State University, Ames.

Photo Credit: photo courtesy of Konrad P. Schmidt, copyright Konrad P. Schmidt.

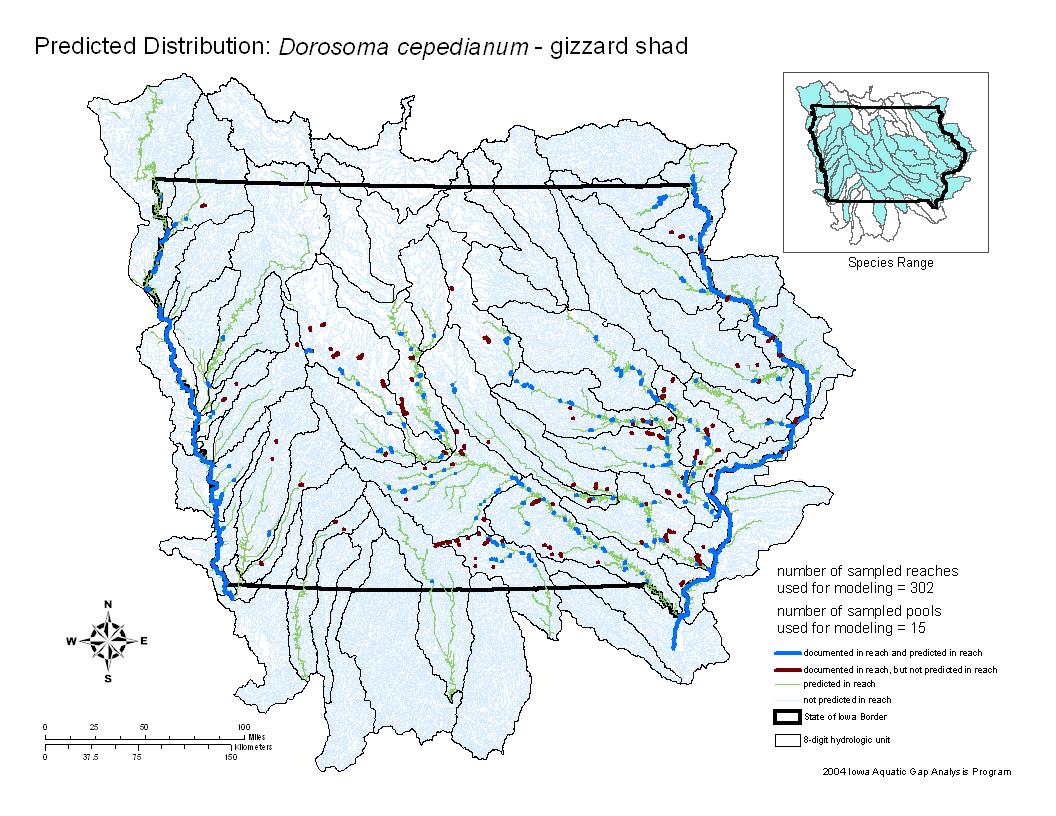

Distribution Map

One of the most widespread and abundant of Iowa’s fish. With the exception of the far north-central part of the state, it has been found in all the state’s major rivers systems, large reservoirs and man-made lakes. It is found throughout the Mississippi River as well as in parts of the Missouri River.

See our most recent distribution data for this species on the Iowa DNR's Bionet application.

State Record(s)

No state record exists for this species

Submit your potential recordMaster Angler Catches

No Master Angler catches currently exist for this species.

Submit your Master Angler catchFish Surveys

Tip: Click Species Length by Site, then use the dropdown to filter by fish species of interest.Where this Fish Is Found

Ada Hayden Heritage Park Lake

Atlantic Quarry Pond 3

Banner Lake (north)

Banner Lake (south)

Big Creek Lake

Big Sioux River

Big Timber Complex

Blue Heron Lake (Raccoon River Park)

Boyer River (Dunlap to Missouri River)

Cedar Lake

Copper Creek

Coralville Reservoir

Des Moines River (Farmington to Keokuk)

Des Moines River (Saylorville to Red Rock)

Des Moines River (Stratford to Saylorville Lake)

DeSoto Bend at DeSoto National Wildlife Refuge

East Nishnabotna River

Easter Lake

Folsom Lake

Grays Lake

Iowa River (Columbus Junction to Mississippi R)

Jay Carlson Pit (west)

Lake Macbride

Lake Manawa

Liberty Centre Pond

Little Sioux River (Correctionville to Missouri R)

Little Sioux River (state line to Linn Grove)

Lower Pine Lake

Missouri River (Council Bluffs to state line)

Missouri River (Little Sioux to Council Bluffs)

Missouri River (Sioux City to Little Sioux)

North Raccoon River (above Auburn)

North Raccoon River (Perry to Van Meter)

Petersons Pit, West

Pool 16, Mississippi River

Pool 17, Mississippi River

Pool 18, Mississippi River

Pool 19, Mississippi River

Prairie Lakes North

Prairie Lakes South

Prairie Park Fishery

Prairie Ridge South

Purple Martin Lakes

RAPP Park Lakes

Red Rock Reservoir

Roberts Creek Lake

Sand Lake

Saylorville Reservoir

Seminole Valley Park Lakes

Terry Trueblood Lake

Tuttle Lake

West Nishnabotna River